From Art Museums to the Supreme Court: How Does the Decision in Warhol v. Goldsmith Go Beyond Art?

*This post is part of a series of resources produced by our Student Research Fellows in Summer 2023. The content does not necessarily reflect the official position of the organization. *

So, What is Warhol v. Goldsmith?

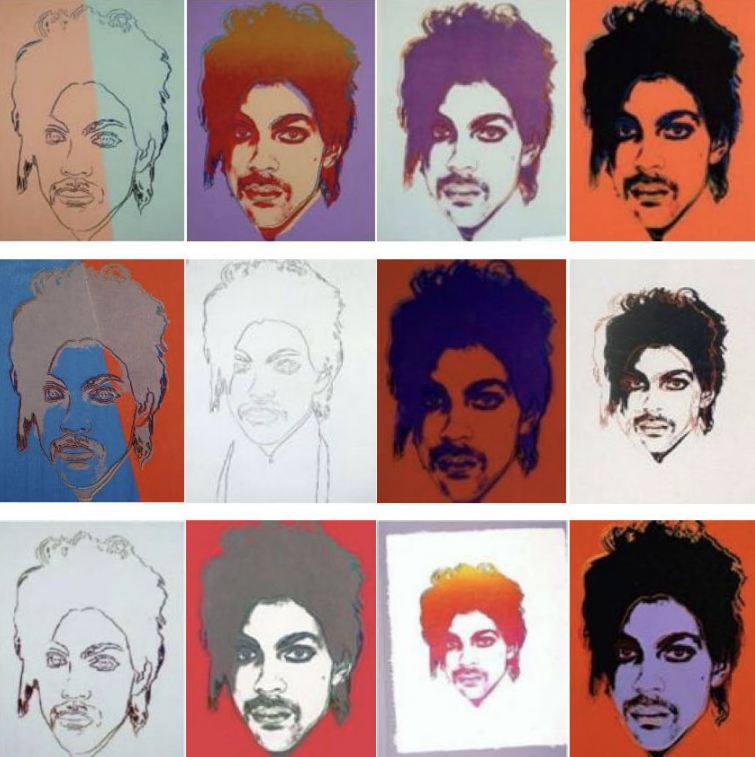

In 1981, before Prince was the Prince of Purple Rain acclaim, he was photographed by Lynn Goldsmith for Newsweek. Years later, in 1984, when Prince was elevated to the status of icon, Vanity Fair paid $400 to use Goldsmith’s photo as a reference for an artist illustration. Goldsmith issued a limited license for a one-time only use of her photograph and was credited as the source when the artist’s work was published. That artist was Andy Warhol, and the resultant 1984 illustration would come to be known as the “Purple Prince.” A purple silkscreen portrait of Prince created in 1984 by Andy Warhol to illustrate an article in Vanity Fair.

A purple silkscreen portrait of Prince created in 1984 by Andy Warhol to illustrate an article in Vanity Fair.

Fast forward to 2016: Prince has just died and Conde Nast – parent company to Vanity Fair – reaches out to the Andy Warhol Foundation (AWF) to reuse the commissioned Warhol illustration for a special edition tribute to the icon. As it turned out, Warhol did not just create “Purple Prince” as featured in the 1984 article, but also a series of other silkscreen prints of Prince in different colors. Conde Nast chose to license “Orange Prince” for the tribute for $10,000, paid to the Andy Warhol Foundation. At no point was Lynn Goldsmith compensated for the reuse of her image. In fact, she claims she only learned about the deal and the existence of the other prints of Prince when she saw an iteration of her photograph on the cover of a magazine.

An orange silkscreen portrait of Prince on the cover of a special edition magazine published in 2016 by Condé Nast.

Goldsmith believes the unauthorized use of her photograph is copyright infringement. The Warhol Foundation believes the works are transformative and thus exempt from copyright infringement under the fair use provision of the Copyright Act. In 2019, the United States District Court granted a motion of summary judgment in favor of Warhol. The decision was then reversed by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, even after the Court was requested to examine the case under the new Google v. Oracle precedent (which applied the transformative use doctrine of fair use to software in favor of Google).

This tumultuous legal battle came to a close when the Supreme Court granted certiorari, meaning they accepted to hear the case. Library Futures filed a joint amicus brief to the Supreme Court, along with the American Library Association and the Association of Research Libraries among others, in favor of neither side. The question for the Court concerned whether or not the Warhol work constituted fair use of Goldsmith’s original photograph.

What Does It All Mean?

In short, the Warhol Foundation lost, and Goldsmith won. While this can be taken as a win for photographers like Goldsmith who rely on the licensing money their images bring in, the decision runs the risk of harming fair use by focusing too much on the commercial nature of the case in determining that the work violates the first factor of fair use (purpose and character of the use).

Goldsmith’s lawyers argue that a looser definition of fair use is responsible for “the gradual erosion of photographers’ rights in favor of famous artists who affix their names to what would otherwise be a derivative work of the photographer and claim fair use by making cosmetic changes.” Yet this statement ignores the dangers of disrupting fair use, which could have large-scale ramifications beyond the arts. Goldsmith’s supporters, like CEO of the Picture Licensing Universal System Coalition Jeffrey Sedlick, find AWF’s view allows “anyone [to] claim a transformative use—and thereby assert an essentially irrebuttable presumption of fair use—merely by claiming a change to the ‘meaning or message’ of a work.” This gross misunderstanding of fair use perpetuates the harmful idea that works protected by fair use are gussied up pieces of plagiarism.

Justice Sotomayor’s majority opinion argues because both the original photograph and the Warhol piece share similar purposes and Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo was commercial that there are no grounds for a fair use finding. She goes on to leash the works’ difference in meaning or message as only worth consideration “to the extent necessary to determine whether the purpose of the use is distinct from the original.” The Court thus elevates the first factor of fair use, purpose of the use (and specifically, how the uses compete against each other commercially), above all else, deciding that it matters little whether or not the two works differ and whether those differences create new meaning. In her dissent, Justice Kagan sums up the majority opinion best: “it is not just that the majority does not realize how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care.” Sotomayor even says herself, “the commercial nature of the use…looms larger.” And thus the discussion of these two works is sanitized down to money.

A black and white portrait photograph of Prince taken in 1981 by Lynn Goldsmith.

Kagan is clear that the majority’s belief that a work’s purpose overshadows all else does a disservice to fair use and “hampers creative progress and undermines creative freedom.” Kagan’s dissent finds that the decision misinterprets the Campbell precedent it relies upon (a notion Sotomayor does not take kindly to in her opinion). The dissent quotes Campbell itself in arguing “the more transformative the new work, the less will be the significance of other factors, like commercialism, that may weigh against a finding of fair use.” These notions were recently reaffirmed in the Google v. Oracle decision.

By choosing to focus largely on the commercial use of the two images, the court ignores the innate artistic value of the two pieces and the distinct value and meaning added to the original photograph by Warhol.

Why Should Librarians Care?

The Association of Research Libraries defines fair use as “permit[ing] the use of copyrighted material without permission from the copyright holder under certain circumstances.” Fair use is regarded as “the most important limitation on the rights of the copyright owner” for libraries and similar public and educational institutions.

The collections libraries possess and make accessible to the public depend on decades of fair use precedent. Without that, libraries would often be unable to provide patrons access to materials without infringing upon copyright. Specifically, the digitization of library materials is largely reliant on libraries’ ability to access and share materials without fear of claims of copyright infringement. Without flexible fair use, the mandate to facilitate research and public learning by providing access to copyrighted materials could be threatened.

Libraries and archivists have independently created and enforced community guidelines or “best practices” of fair use, practices which could be threatened by government interference – like the court’s altering the way fair use of works is determined.

Warhol v. Goldsmith is more than a licensing dispute. It is a grudge match between the justices over the meaning of key precedents like Campbell and the way the factors of fair use weigh against each other. In years to come, this case may be seen as the precursor to a shift in fair use jurisprudence. It is crucial that all who rely on fair use, including libraries, are paying attention.

What Happens Next?

In the wake of the Warhol v. Goldsmith Supreme Court opinion, there remains a large measure of uncertainty about the future of fair use. The likely – and hopeful – outcome is that this opinion, in spite of all fears, will impact little beyond the narrow world of appropriation art – art that, like Warhol’s, transforms pre-existing works into new pieces with new meaning.

The opinion depends heavily on the determination that the purpose of the use for both photographs is commercial, relying on the precedent set in Campbell, which distinguished between commercial uses and non-profit and educational uses. This narrowness bodes favorably for libraries and research institutions because their use of work falls in the latter category.

Yet there will continue to be the possibility that the Warhol v. Goldsmith decision forebodes a domino-like degradation of protection of fair use, which will depend on the lower court’s interpretation of this new precedent in future cases. In Artnet News, New York University law professor Amy Adler shares her advice for most artists seeking legal advice: “I would probably warn them that it’s just simply too dangerous to refer to pre-existing work…. There’s gonna be a lot more litigation trying to flesh out exactly what this new interpretation means.” There is no true prediction as to how this precedent will impact areas outside of the arts, though that risk is looming.

Lower courts may find this decision to be a drastic narrowing of fair use, one that emphasizes a work’s commercial nature over any other fair use factor, thus making it difficult for a variety of works to qualify as fair use. Further, if the opinion is interpreted as saying that a work may be fair use until it is licensed for commercial use, it could create a situation where artists retain “a residual interest in the new work.” Jonathan Ellis, former assistant to the solicitor general of the United States, describes this potential impact as, “Every subsequent use of the new work must pass the fair-use test anew—without regard to the transformative nature of the work’s creation itself.”

The storm cloud possibility that Warhol is the start of a degradation of fair use protections will hang above us until future litigation diminishes its likelihood (or makes these fears a reality). For now, though, fair use should hold strong as a cornerstone of the rights of creators and institutions of access in the digital age. * Image Attribution: All images included in this post are reused from the Supreme Court majority opinion by Justice Sotomayor.*

References

Aiwuyor, J. (2022, February 14). Libraries, universities, and civil society groups to celebrate Fair Use/Fair Dealing Week 2022 on February 21–25. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.arl.org/news/libraries-universities-and-civil-society-groups-to-celebrate-fair-use-fair-dealing-week-2022-on-february-21-25/

American Library Association. (n.d). Copyright for libraries: fair use. https://libguides.ala.org/copyright/fairuse

Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 21-869 (US Supreme Court 2023). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/22pdf/21-869_87ad.pdf

Association of Research Libraries. (n.d). Code of best practices in fair use for academic and research libraries. https://www.arl.org/code-of-best-practices-in-fair-use-for-academic-and-research-libraries

Association of Research Libraries. (n.d). Fair use. https://www.arl.org/fair-use/

Association of Research Libraries. (n.d). Know your copyrights. https://www.arl.org/know-your-copyrights/

Brief of Library Futures Institute, the Software Preservation Network, the EveryLibrary Institute, the American Library Association, the Association of College and Research Libraries, and the Association of Research Libraries in Support of Neither Party, Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith and Lynn Goldsmith, LTD., 21-869 (2023). https://www.supremecourt.gov/DocketPDF/21/21-869/228252/20220617095802802_21-869_Amici%20Brief.pdf

Brittain, B. (2023, May 19). Warhol estate loses U.S. Supreme Court copyright battle over Prince artwork. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/legal/warhol-estate-loses-us-supreme-court-copyright-fight-over-prince-paintings-2023-05-18/

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994). https://www.oyez.org/cases/1993/92-1292

Cascone, S. (2023, May 26). Did the Supreme Court’s Warhol decision further complicate copyright law? Experts weigh in on the ruling’s ramifications. Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/art-world/warhol-goldsmith-prince-ruling-fallout-2307975

Daley, J. (2019, July 13). Warhol’s Prince image doesn’t violate copyright judge rules. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/warhols-prince-image-doesnt-violate-copyright-judge-rules-180972559/

Every Library Institute. (2022, June 29). ELI joins amicus brief in Andy Warhol Foundation v Goldsmith. https://www.everylibraryinstitute.org/amicus_brief_warhol

Goldrich, A. (2022, October 6). Why does the United States government want to talk to the Supreme Court about Andy Warhol? Artnet News. https://news.artnet.com/opinion/why-does-the-united-states-government-want-to-talk-about-andy-warhol-2187870

Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc., 593 (US Supreme Court 2021). https://www.oyez.org/cases/2020/18-956

Harvard Law Review. (2021, November 10). Comment on: Google LLC v. Oracle America, Inc. 135 Harv. L. Rev. 431. https://harvardlawreview.org/print/vol-135/google-llc-v-oracle-america-inc/#:~:text=Last%20Term%2C%20in%20Google%20LLC,as%20a%20matter%20of%20law

Jolly, J. (2023, May 30). Warhol, art, and capitalism before the Supreme Court. The Edge Media. https://www.theedgemedia.org/warhol-art-and-capitalism-before-supreme-court/

Klosek, K. (2021, February 22). We’re all fair users now. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.arl.org/blog/were-all-fair-users-now/

Klosek, K. (2022, February 18). Fair use supports research, journalism, and truth. Association of Research Libraries. https://www.arl.org/blog/fair-use-supports-research-journalism-and-truth/

Labate, R., Pinkins, P., & Gierhart, C. (2023, June 15). U.S. Supreme Court holds that first factor of fair use test favors photographer. Holland & Knight. https://www.hklaw.com/en/insights/publications/2023/06/us-supreme-court-holds-that-first-factor-of-fair-use

MOMA Learning. (n.d). Pop art. https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/themes/pop-art/appropriation/

Wherry, T. (2002). The librarian’s guide to intellectual property in the digital age: copyrights, patents, and trademark. American Library Association. https://www.ala.org/aboutala/sites/ala.org.aboutala/files/content/publishing/editions/samplers/wherryt_IP.pdf

About the Author

Bella Wetherington is preparing to start her second year of law school at Georgetown University Law Center and hopes to use her legal education in the areas of media, entertainment, technology, and the arts.