Mapping the Bronx: Where Digital Redlining Denies Access and How Libraries Can Help

This post is part of a series of resources produced by our Student Research Fellows in Summer 2023. The content does not necessarily reflect the official position of the organization.

During the pandemic my family often traveled from Central Pennsylvania to my mother’s home in the Bronx for support with childcare while I was enrolled in graduate school. Though the support was helpful, I struggled with participation in class because I often had weak internet connections during my course work and tutoring duties. I tried to find the best spots in the apartment so Zoom freezing would be minimal, but it was hard to do in a one-bedroom apartment with six people. Ultimately, I stayed in a corner of my mother’s bedroom and hoped for the best. The poor internet connectivity also impacted my mother’s ability to teach remotely. It didn’t seem to matter whether we stopped TV streaming or disconnected our phones from the wifi while we were on Zoom. My mother had even changed her router twice with her internet provider in the past three years and yet her internet connectivity was still weak. It wasn’t until recently I began to understand what seemed to be occurring – digital redlining.

Redlining is part of the long history of racism within the United States, and the Bronx’s geography was particularly impacted by structural racism. I grew up hearing stories about the Bronx burning due to landlords hiring arsonists so they could collect insurance money. Redlining has a long history of demarcating where Black residents could live across the country, and it still has consequences today. Redlining refers to the way the Federal Housing Administration historically refused to insure the mortgages in Black neighborhoods. Neighborhoods that were denied insurance still display health disparities, have negative birth outcomes, and lack food access. Scholars also argue redlining reduces or limits internet access, a practice known as digital redlining.

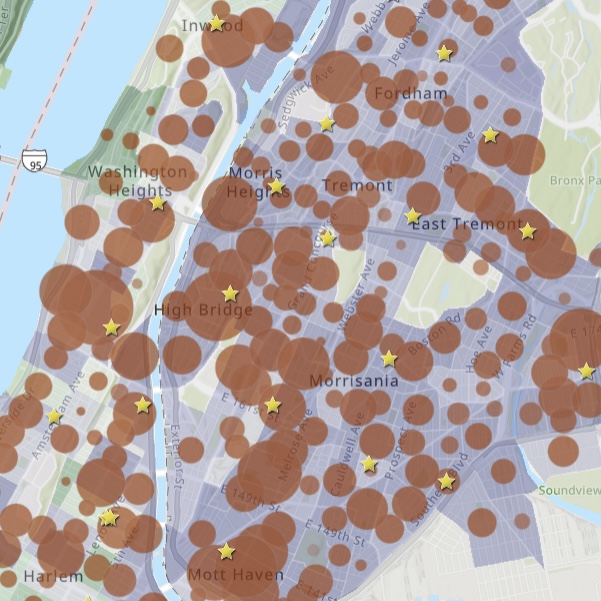

Scholarship on digital redlining has been steadily increasing and highlighting how lack of high-speed internet has affected low-income communities. Additionally, the data make it clear that many low-income communities are also communities of color, which is not a coincidence. I created a map with ArcGIS using 10 years of data from the U.S. Census Bureau to visualize which communities in the Bronx lack internet access along with their income levels. What the map reveals, as other scholars have pointed out, is lower-income communities do not have access to high-speed internet, so they must turn to shared resources, such as public libraries, which are not always resourced for the population size they must serve in response. Residents of digitally redlined communities are more likely to experience health inequities, such as inability to attend telehealth appointments or obtain COVID-19 vaccines. Digital redlining also affected educational gaps amongst children during the pandemic.

Along with digital redlining comes information redlining, which American Library Association Director Tracie D. Hall defines as “the systematic denial of equitable access to information, information services, and information retrieval methods.” While digital redlining focuses on access to internet connectivity, information redlining centers on broader access to information services, access, and retrieval. Hall notes that Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately affected and therefore have fewer job opportunities and less economic mobility. Digital and information redlining merge when connectivity prevents information access. When tied to the history of redlining, both become purposeful attacks on low-income residents. Hall believes libraries can play a “primary role” in the elimination of information poverty.

In 2010, the U.S. Impact Study was released, noting a large number of people in the United States are reliant on libraries for internet access. About thirteen years later, libraries still play a crucial role in providing internet access. The interactive map I created highlights this by using data from the American Community Survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau to visualize internet access and average household incomes in the Bronx, New York. Internet connection data are displayed in red circles on the map, with larger circles noting higher populations of households that lack internet connection. Income data is displayed by county with darker purples indicating lower income communities and green representing communities with higher incomes. The map is interactive, and users can click on the county or circle to learn more about the percentage of households with lower internet access or the average household income for the area. The map also includes public library locations, which are marked with yellow stars. When clicking on the yellow stars, users will learn branch details, including public service hours per year. I focused on where I grew up in the Bronx, New York, to visualize how residents are affected by digital redlining. With this project, I hope people can recognize how marginalized communities are impacted by digital redlining, particularly in New York City.

Click the double arrows in the upper left corner of the map to toggle the legend and map details. Zoom in and out to see more population data.

Working with this data set was a surreal experience – I felt like my family and close ones were part of a data set that confirms these disparities. Flashes of interrupted connection while uploading Canvas assignments or Zoom freezing in the middle of a meeting came to mind as I searched the map. Despite my initial focus on the Bronx, searches on the map revealed patterns of lower income communities with less access to internet connectivity. The library locations also serve as a visualization of where residents would have to travel to access free, reliable internet via a public library.

What I saw in the data confirmed years of lived experience around systemic racism and its impact on low-income communities of color. The Bronx is one of five New York City boroughs with the highest number of residents living in poverty and has the lowest penetration of internet access. It also has only 35 libraries that its 1.5 million residents share. To break that down, if each borough served an even amount of patrons, that would mean roughly 40,000 Bronx residents designated to a single building. Comparatively, a university or college has an average enrollment of 6,000 students. Even then, those students usually have access to a few libraries and other spaces that provide internet, books, and the information they need.

In Places Journal, Shannon Mattern writes about libraries as infrastructure. Mattern discusses how seeing the library as a platform can be limiting and contrasts that with the ways the library performs as a social (and physical) infrastructure. Libraries have evolved into sites where the disfranchised can gather resources and develop knowledge that otherwise are kept away from them, whether through ESL classes, career services, or other resources like COVID-19 tests. Libraries have also been instrumental for many low-income residents to obtain reliable internet and digital resources. Some libraries have even done the footwork to bring high-speed internet directly to their residents.

While these issues may seem intractable for libraries, the New York Public Library’s borough branches have steadily created programs and digital resources so different communities can access information that can help to close disparities. For example, six branches across the Bronx, Manhattan, and Staten Island are currently providing free wifi to New York City residents, serving as an example of how libraries can address digital and information redlining.

Though this project focused on equity issues in the Bronx, the data collected in the map covers the entire United States. Viewers can input their desired location in the “find address or place” search bar to visualize internet access, average household income, and public library access for their local community. If libraries are to address digital disparities, they must have support from others who want to take action against information poverty. One way to stay informed about the ways you can support libraries in improving access for all is by following Library Futures on social media and signing up as a Library Futures Insider.

References

About the American Community Survey. (n.d.) U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/about.html

Amin, R. (2022, January 6). NYC schools failed to provide students with adequate remote learning access: Lawsuit. Chalkbeat New York. https://ny.chalkbeat.org/2022/1/6/22870943/nyc-schools-remote-learning-lawsuit

Batch, K. (2020, September). A case study of two tribally-owned fiber networks and the role of libraries in making it happen. ALA Policy Perspectives, 1-22. https://www.ala.org/advocacy/sites/ala.org.advocacy/files/content/telecom/erate/Built_by_E-Rate_WEB_090420.pdf

Becker, S., Crandall, M. D., Fisher, K. E., Kinney, B., Landry, C., & Rocha, A. (2010, March). Opportunity for all: How the American public benefits from internet access at U.S. libraries. Institute of Museum and Library Services. https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/publications/documents/opportunityforall_0.pdf

Clare, C. A. (2021). Telehealth and the digital divide as a social determinant of health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics, 10(1), 26. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8019343/

Gonzalez, D. (2022, January 20). How fire defined the Bronx, and us. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/20/nyregion/bronx-fires.html

Gross, T. (2017, May 3). A 'Forgotten History' of how the U.S. Government segregated America. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2017/05/03/526655831/a-forgotten-history-of-how-the-u-s-government-segregated-america

Hall, T. D. (2020, November 2). Ending information redlining: The role of libraries in the wave of the civil rights movement. American Libraries. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2020/11/02/ending-information-redlining/

Huang, S. J., & Sehgal, N. J. (2022). Association of historic redlining and present-day health in Baltimore. PloS One, 17(1), e0261028. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261028

Mattern, S. (2014, June). Library as infrastructure. Places Journal. https://doi.org/10.22269/140609

McCall, T., Asuzu, K., Oladele, C. R., Leung, T. I., & Wang, K. H. (2022). A socio-ecological approach to addressing digital redlining in the United States: A call to action for health equity. Frontiers in Digital Health, 4, 897250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdgth.2022.897250

Michaels, I. H., Pirani, S. J., & Carrascal, A. (2021, August 26). Disparities in internet access and COVID-19 vaccination in New York City. Preventing Chronic Disease, 18. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210143

Nardone, A. L., Casey, J. A., Rudolph, K. E., Karasek, D., Mujahid, M., & Morello-Frosch, R. (2020). Associations between historical redlining and birth outcomes from 2006 through 2015 in California. PloS One, 15(8), e0237241. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237241

NYPL Wireless. (2023). New York Public Library. Retrieved August 2023 from https://www.nypl.org/spotlight/nypl-wireless

Report: Public libraries essential to closing digital divide. (2022, March 29). Government Technology. https://www.govtech.com/civic/report-public-libraries-essential-to-closing-digital-divide

Shaker, Y., Grineski, S. E., Collins, T. W., & Flores, A. B. (2023). Redlining, racism and food access in U.S. urban cores. Agriculture and Human Values, 40(1), 101–112. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9303837/

Skinner, B., Levy, H., & Burtch, T. (2023, April). Digital redlining: The relevance of 20th century housing policy to 21st century broadband access and education. EdWorkingPaper No. 21-471. https://doi.org/10.26300/q9av-9c93

Understand college campus and student body size. (n.d.) BigFuture. https://bigfuture.collegeboard.org/plan-for-college/college-basics/types-of-colleges/understand-college-campus-student-body-size

About the Author

Wendyliz Martinez is a PhD candidate in English and African American Studies at Penn State University. She is currently writing her dissertation, Secret Lives of Black Girls: Interiority and Black Girlhood in Film, Literature, and Social Media. Her research interests include representations of the Caribbean and Black girlhood in literature, film, and social media, as well as digital humanities more broadly.